The imposition of Eurocentric history on colonized cultures and societies established a “civilized vs. uncivilized” binary that supported and enforced colonialist, imperialist, and racist hierarchies while simultaneously misrepresenting (and attempting to erase) more ancient and enduring African, Indigenous, and Asian understandings of intercultural trade, science, agriculture, and social development/structure.

Modern Eurocentric (19th-century forward) trans+ history traces the emergence, visibility, and evolving social, medical, and political understandings of gender diversity from the 1850s CE to the present. While gender-diverse people have existed in every culture throughout recorded history, the recent era marks a shift in how Western societies conceptualize, categorize, legalize (or make illegal), and respond to people whose gender identities and expression may not align with the gender role they were assigned at birth.

Impactful developments include anthropological discoveries related to evolution, and emerging science that replaced mythological beliefs about the origins of human sexual and identity variations in the fields of sociology, sexology, genetics, endocrinology, psychology, and psychiatry, all of which contributed to a rise in global human rights movements.

Read below for modern Eurocentric knowledge systems.

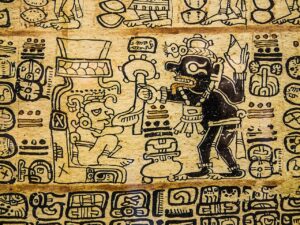

Some Indigenous cultures developed their own writing (textual) systems long before European arrival, others in the 18th–20th centuries, often for political, cultural, or religious mobilization.

A majority of Indigenous cultures throughout history never developed written language, relying instead on non-textual systems for recording events, such as:

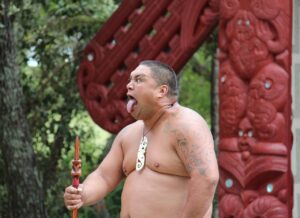

The collective body of cultural knowledge—stories, histories, songs, teachings, genealogies, rituals, instructions, and explanations—that is preserved and transmitted by speaking, reciting, performing, or singing, often across many generations.

A community-designated knowledge keeper responsible for preserving, transmitting, and interpreting the collective memory of a people.

Memory aids—strategies, techniques, or tools that help people remember information more easily. They work by connecting new information to something more familiar, vivid, or structured, making it easier for the brain to store and recall.

Physical objects, forms, or visual motifs created, used, or maintained by Indigenous peoples that carry culturally specific meaning, often relating to identity, cosmology, social structure, ancestry, land relationships, or spiritual practices.

The ways Indigenous peoples understand the origins, structure, and ongoing relationships of the universe encompassing the sky, the earth, the living world, the spirit world, and humanity’s place within these interconnected systems. Not a “belief system” in the Western sense; it is a living, relational, land-based framework that shapes ethics, knowledge, identity, and community life.

Indigenous cosmology is not hierarchical in that humans are not placed above nature, but have interwoven relationships with animals, plants, water, land, and non-human entities.

Indigenous ritual transmission is the culturally specific process by which Indigenous communities preserve, teach, adapt, and enact ceremonial knowledge across generations. It involves relational, embodied, and often sacred forms of learning that maintain continuity with ancestral traditions while allowing for culturally guided change. This transmission typically occurs through oral teachings, lived participation, observation, mentorship by elders or ritual specialists, and the fulfillment of family or clan responsibilities.

Indigenous ritual transmission sustains cultural identity, preserves ecological and cosmological knowledge, strengthens community cohesion, and protects traditions from loss, appropriation, or dilution.

Before the 1850s, humans were understood to be individually created by a “Supreme Being”, and part of a “Divine Order”.